The Rosetta Stone and the Age of Forgetting

Humans forget. We forget far more than we remember. I’ve lived long enough now to know that forgetting is a fundamental process that undergirds all human knowledge of ourselves and our history. We have limited capacity for recollection. And we have a limited capacity to recognize what is worth remembering. And much of the information we generate is worth forgetting. How do we sort out the worthwhile ideas from the superfluous?

Memory is the bedrock of identity and of civilization itself. Paradoxically, we find ourselves in an era when surrounded by many treasures of human knowledge made readily available, we are forgetting more and more. We are facing a curious crisis: the Information Age is becoming the Age of Forgetting.

Increasingly, it would seem as though with all our advanced technological systems for storing and referencing knowledge, the information age is becoming an illiterate age too. We live in an era where information is available at the click of a button. Yet, with all this knowledge, reading literacy is in decline, particularly among the young.

In a recent article in The Atlantic titled The Elite College Students Who Can’t Read Books, we learn that many professors at our most elite universities are encountering fresh students “overwhelmed” by the expectations to read books:

“Dames’s students now seem bewildered by the thought of finishing multiple books a semester. His colleagues have noticed the same problem. Many students no longer arrive at college—even at highly selective, elite colleges—prepared to read books.”

These students, accustomed to the fragmented and instant gratification of digital media, find themselves bewildered by the discipline of sustained reading. Primary school students struggle with reading comprehension, while college students, many from top-tier institutions, find themselves ill-prepared for the intellectual labor that their predecessors took for granted. What does it mean that in an age of knowledge, where entire libraries are digitized and available at our fingertips, so few are equipped to truly learn from them? It is not information they lack, but the ability to engage with it deeply, face to face. Reading ability for students in primary education also has seen significant decline over the last few decades and attention spans continue to wane.

Focus is an increasingly rare skill.

Professor Jonathon Haidt writes and lectures extensively about the challenges he observes in his classrooms at NYU with “coddled” students who demand protection from ideas that challenge their sensibilities and the challenge of teaching students with ever limited attention spans. The role of smartphones, ever present connectivity, and social media platforms are contributing to both a crisis of attention span and a crisis of courage that threatens the project of primary and higher education.

The result?

A narrowing of intellectual horizons and a retreat into echo chambers of thought. Students, conditioned by the quick consumption of social media, find it harder to engage with complex, uncomfortable, or slow-moving ideas. The immediate access to information has, in many cases, become a barrier to wisdom rather than a bridge.

It is no coincidence that these trends align with a decline in reading skills and focus. Reading deeply, after all, requires sustained attention, a willingness to wrestle with ideas over time. It demands that the reader engage with the material not as a passive consumer but as an active participant. Yet the tools of our age encourage the opposite. Instant access, notifications, and the constant hum of digital distraction work against the very habits that foster deep learning.

Academia in large part avoids teaching close reading in favor of jargon filled pre-determined postmodern analysis obsessed with identifying the oppressor and the oppressed, which has further distanced students from meaningful engagement with texts. These trends, alongside the rise of identity politics and critical theory-heavy approaches, contribute to students’ struggles with reading dense material. As literature departments lean into theoretical frameworks, the basic skill of "reading" in the sense of deep comprehension and critical thinking is often neglected. When you already know the “right answers,” why spend the time to fully become introduced to an old idea?

The crisis in literacy echoes a broader question: how does humanity transmit wisdom forward while staying connected to the sources of that wisdom?

This is not a new problem. The concerns of educators today mirror concerns that have persisted throughout Western Civilization. The threat of human forgetfulness and in-attention are recurring themes stretching back thousands of years.

Ancient Egyptians and ancient Greeks feared how the use of the written word might result in a loss of wisdom. Stretching back to the inception of the written word, a tension persists between information and wisdom, between learning and understanding, forgetting and knowing.

In the pages of Plato's "Phaedrus," Socrates cast a skeptical eye on the practice of writing, sharing a myth about Thoth, the Egyptian god credited with inventing writing, who presents his creation to King Thamus. Thoth eagerly believes he's offering writing as a tool to store wisdom and memory.

But King Thamus voices reservations:

“…you who are the father of letters, from a paternal love of your own children have been led to attribute to them a quality which they cannot have; for this discovery of yours will create forgetfulness in the learners' souls, because they will not use their memories; they will trust to the external written characters and not remember of themselves. The specific which you have discovered is an aid not to memory, but to reminiscence, and you give your disciples not truth, but only the semblance of truth; they will be hearers of many things and will have learned nothing; they will appear to be omniscient and will generally know nothing; they will be tiresome company, having the show of wisdom without the reality.”

These Socratic concerns about the positive and negative effects of technologies can certainly be understood by anyone alive today. It’s not hard to extend these concerns to artificial intelligence and other such knowledge systems and tools.

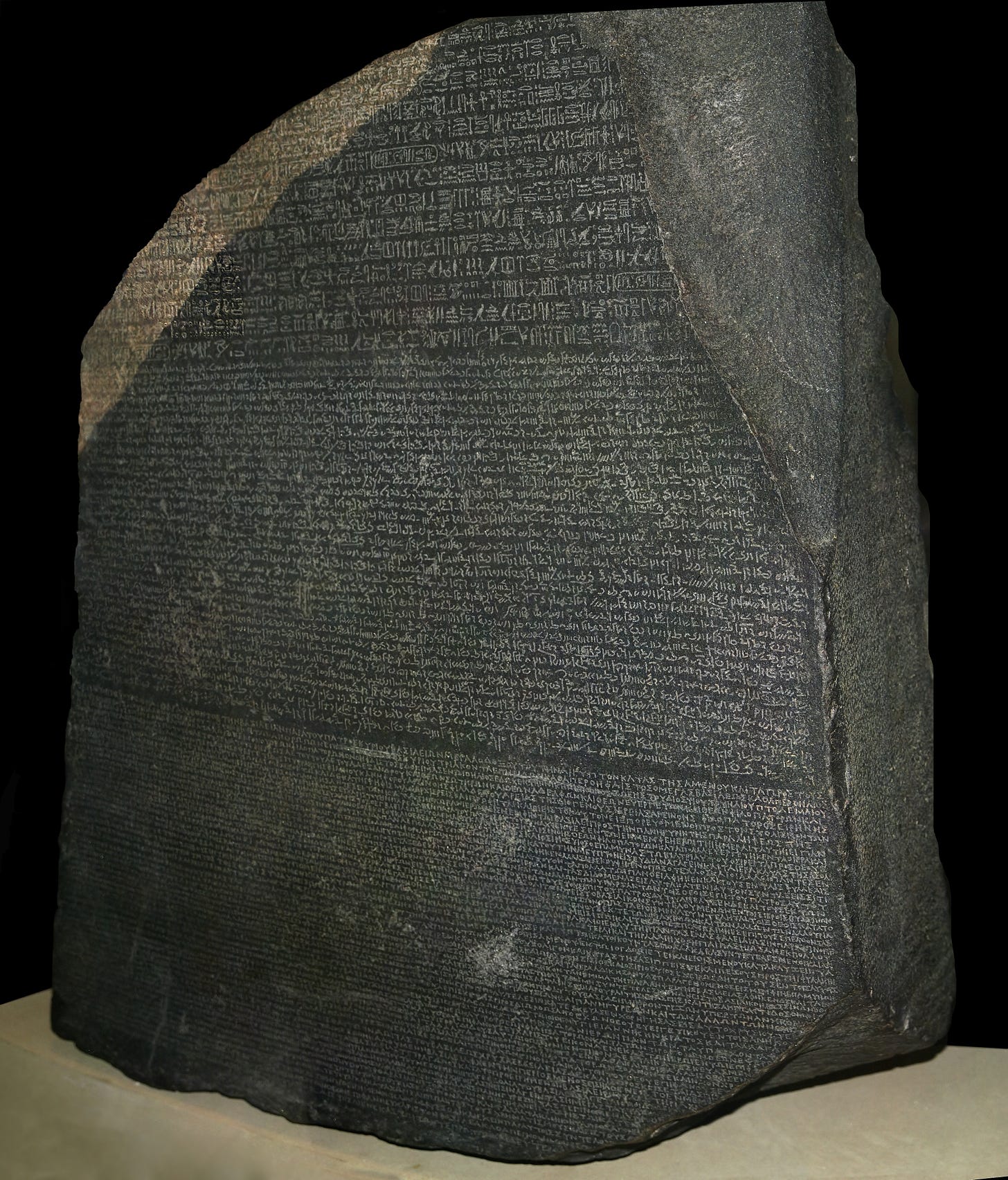

The Rosetta Stone serves as a symbol of this struggle to present ideas and project them into the future. Discovered in 1799, this massive granodiorite rock slab, standing nearly four feet tall, over two feet wide, and weighing 1,680 pounds, bears inscriptions in three languages: Greek, Demotic, and Egyptian hieroglyphs. Its very physicality speaks to humanity's desire to pass forward knowledge; the ancient Egyptians chose this immensely heavy, durable stone because they understood the precariousness of memory and the need to reinscribe important truths.

Created in 196 BC during the Ptolemaic dynasty, the stones were commissioned by a council of priests to commemorate King Ptolemy V Epiphanes and was meant to be displayed in every temple across Egypt as a form of royal proclamation. The mandate for multiple copies across temples reveals a reality of our human condition that important ideas require repeated presentation to be remembered. Though its original decree celebrating the first anniversary of Ptolemy V's coronation is now unimportant politically, its true significance emerged centuries later.

The stone's trilingual inscription, with its hieroglyphs lightly incised on the polished surface, allowed scholars to bridge the gap between Ancient Egyptian and modern language, unlocking the secrets of a long-forgotten culture and history. At the time of its discovery, no one had been able to read Egyptian hieroglyphs for centuries. While scholars could understand the Greek section of the text, the real challenge was unlocking the meaning of the hieroglyphs. The stone’s rediscovery allowed modern scholars to recover an entire civilization’s lost language, opening up centuries of Egyptian history to scholars. In this sense, the Rosetta Stone is not just a tool for decoding language; it is a symbol of the human capacity to recover lost wisdom.

The Rosetta Stone reminds us that knowledge, languages and cultures, if not actively preserved and integrated, will be lost to time. Wisdom is constantly being lost. There are no guarantees that any idea will survive into the future.

Today we face a barrage of media competing for attention, much of it visual, all fragmented. Want to learn about the Rosetta Stone? No problem. Many pictures, videos, articles, historical readings and interpretations are available. But, perhaps those memes your friend sent will get looked at first, and then perhaps you are caught in a doom scroll and with it the great ideas are doomed by distraction.

We live in a culture overwhelmed by visual stimuli, which diminishes our capacity for the kind of focused attention that reading requires. This fractured attention is part of the crisis, as traditional forms of deep, focused reading become increasingly rare. Reading is not just about decoding text but engaging deeply with ideas, something that digital culture undermines by privileging speed and surface-level engagement.

It’s not hard to think that contemporary technology may create people with shallow knowledge that seem informed when they've only scratched the surface of true understanding. Without experience that comes from dialogue and a challenge to our ideas, understanding remains superficial.

So, how can we continue to transmit deep intellectual traditions in an era that increasingly prizes immediacy and utility and political correctness over contemplation and understanding? Is the Rosetta Stone worthy of our attentions at all? This is not an easy set of tasks, but it is a necessary one.

If we are to combat the crisis of attention in modern life, we must instill within ourselves a sense of the continuity of knowledge. Just as the Rosetta Stone connects ancient Egypt to the modern world, we ought to remain connected to the rich intellectual heritage of centuries past, which is our heritage. If we are to foster a culture capable of engaging with the important ideas and questions of history, issues that shaped civilizations, that define our understanding of justice, beauty, and truth, we must hone our capacity for attention, focus, dialogue, logic and intuition. Humans need to engage our attentions with the meaningful. True learning requires active participation with ideas, contending, wrestling, pushing.

There is a need for wisdom, a wisdom that comes not from mere information, but from a deeper engagement with the world through open dialogue, careful study of the past and to acknowledge that forgetting ideas is much easier than keeping them alive.

The myriad of ways that knowledge is lost to time are all reasons to pursue knowledge in the past, present and future.

The informatin age is the age of forgetting. Well said. Cheers!