The Gardens of the North America

Conservation, Wilderness and the life of the forest

“In God's wildness lies the hope of the world - the great fresh unblighted, unredeemed wilderness. The galling harness of civilization drops off, and wounds heal ere we are aware.” ― John Muir

“Wilderness is not a luxury but a necessity of the human spirit, and as vital to our lives as water and good bread. A civilization which destroys what little remains of the wild, the spare, the original, is cutting itself off from its origins and betraying the principle of civilization itself.” ― Edward Abbey

So much of our shared ideas about wilderness in the American West are influenced by the legacies of John Muir, William E. Colby, Ansel Adams, Eliot Porter, Edward Abbey, and many others. The destructive power of clear-cut logging, mining, and other resource extraction is still evident over the whole of the American West, California, and the greater Monterey Bay areas. In an effort to stop all of the old-growth forests of the American West from disappearing, John Muir formed the Sierra Club to conserve portions of the landscape from industry. National parks, national preserves, and state and county parks were created to protect and preserve lands from development. These efforts were in many ways a great success. We greatly benefit from the early efforts to protect these beautiful places where all can recreate and enjoy the natural world.

Since the early 1900s different approaches to management of these natural resources have been explored. Forest fire suppression, thinning of the forest, Wilderness Designations, and prescribed fire, all are ways to manage the forests of the West to support all forms of life.

Until recently, little academic research focused on forest management before the arrival of Europeans. Over the previous 20 years, more and more research is being published regarding the documentation of Indigenous peoples actively and continually tending to and shaping the natural world to be more hospitiable and supportive of human life. A new book published this year by Dr. Lee Klinger highlights both new original research in the Big Sur forests and academic and cultural documentation of prescribed burning and other Indigenous methods that stretch back as far as human memory.

Dr Lee explains in his wonderfully concise and practical book, Forged by Fire: The Cultural Tending of Trees and Forests in Big Sur and Beyond that the forests and landscapes of North and South America and other places around the world were the result of long term human wisdom and tending of the natural world.

“…I have come to learn that a common trait among most of the world's Indigenous Peoples, both past and present, is the cultural practice of tending trees. …Indigenous Peoples, from the tropics to the subarctic and subantarctic, thrived and are still thriving among forests they have cultivated for millennia. Through reciprocal acts of tending the plants and soils, and receiving their sustenance, the People have learned how to best fill their various niches in the forest and help maintain a long-term relationship. That is why, today, we find the vast majority of the world's biodiversity hotspots on Indigenous lands.” ― Dr Lee Klinger

The sources Dr Klinger cites come from all over the globe spanning many scientific disciplines oncluding archeology, geology, biology, history and testimonies of Indigenous peoples the world over. Dr Lee convincingly argues that human wisdom and human care co-created the forested landscapes that in the American West captured the imaginations of the public and inpart inspired the conservation movement.

The idea that the cultivation of forests over milenia is responsible for the great forests and old-growth trees of Big Sur transformed my perspective of wild places.

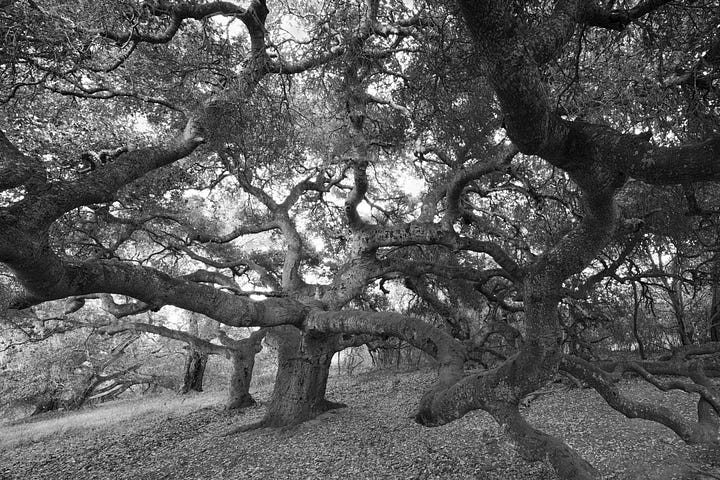

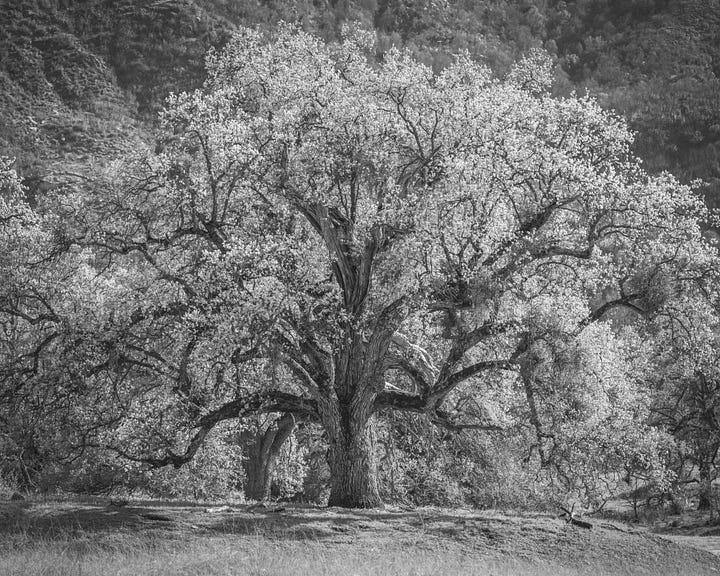

My whole life, looking up into forest canopies, climbing trees and spending time beneath ancient groves has been awe-inspiring. The Ancient Bristlecone pines, Giant Sequois, Giant Redwoods are part of megaflora that inspire in me a desire to contribute to the continuation of the life of these large species of life. Few things manage at once to humble me and encourage me as being among the giant trees of California.

There are many, many places within the Big Sur range of mountains and coastal forest where I can sit and think and be in the presence of giant ancient trees. Redwood temples, old-growth Oak savannah, mighty Manzanitas, Monterey Cyprus, and Pines and Sycamore trees are among the most beautiful places that I visit. The tragic reality of these old-growth groves is that they represent a fraction of what the forest was, but 100 years ago.

One critical piece of evidence Dr Klinger highlights is the presence of shell mounds upon which old-growth trees are growing. The Indigenous peoples of the Big Sur area, Esselen, Ohlone, Salinan and Rumsen, harvested mussels, abalone, clams and other sea life and transported these shells to mounds all over the Santa Lucia Mountains many miles above the coast. This significant effort over thousands of years were part of an integrated cultural, spiritual and ecologically supportive practices that fertilized the soils and supported the life of the forest. To see at the base of old-growth trees the fragments of shells suggests a human wisdom at work over many centuries.

To stand in the middle of an ancient redwood temple and imagine the time and attention required to protect those trees is to contemplate a humbling mystery. Thousands of people over thousands of years developed a culture of care and concern for a rich overstory of trees that are a beautiful and fragile monument to human potential and vision.

That these ancient old-growth trees are largely gone from North America is a tragedy with less than 5% still alive compared to what thrived for centuries before Europeans visited the continent. Almost all old-growth persists within conserved areas such as National Parks and other preserves.

One theory about this trees is that they are the product of a human culture working with natural processes to modify and augment the environment to support the life of the world and the many diverse species within. The opposing theory is that these olg-growth forests were a process of nature and the habitation of humans within and the culture of these peoples played little part in their evolution. Joan Maloof is one example of academics that believe:

“An old-growth forest is one that has formed naturally over a long period of time with little or no disturbance from humankind. They are increasingly rare and largely misunderstood.” Joan Maloof, Nature's Temples: The Complex World of Old-Growth Forests

Most approaches to old-growth forests today is to protect and preserve these places to keep people away. Preventing old-growth from being logged is a critically important work. But are these forests going to re-establish centuries old trees without the helping hands of human?

Certainly I am no expert.

The arguments put forth from Dr Klinger seems properly respectful of the evidence on the ground as I’ve experienced it and his ideas incorporate the testimony of Indigenous peoples alive today about cultural practices of using fire and other methods to tend to the health of the forest. Much historical records from the Spanish and other Eurpeans in North American support the widepsread use of fire by Indigenous peoples. Ideas from people like Joan Maloof generally ignore the presence and significance of Indigenous people and their witness and history and contribution to the life of the forest.

In Don Usner and Paul Henson’s wonderful book The Natural History of Big Sur they write:

“Native Americans in many parts of California deliberately used fires to make the land more productive. The natives burned to improve wildlife habitat and to encourage the production of edible plants and seedproducing oaks and pines. Salinans and Costanoans (also known as Ohlone) periodically burned grassland and oak woodland, and these fires must have spread into the mountains at least occasionally. The Esselen of the Big Sur area probably burned in a similar fashion.

Human-caused and lightning-caused fires continued during the Spanish-Mexican period (1800-1847), but records of how often and where these fires occurred were not kept. Spanish diaries from the period indicate that natives continued burning. Other records indicate that loss of summer and fall livestock forage led the missions to ban native burning. As the natives left their homelands to join the missions, much of the Big Sur coast outside the northern ranchos became very sparsely inhabited during this period and was probably subject to less frequent fire than before European settlement.”

Finding these old-growth trees on public lands, and photographing them will be a background project of mine. Over time as I accumulate photographs, I will publish a gallery. In the mean time, here are a few pictures from around Big Sur of likely culturally modified trees.

I’ll leave you with a section from the forward to Dr Klinger’s book written by Tom Little Bear Nason:

“It's sometimes difficult for me to talk about the loss of ancient forests in Big Sur, products of thousands of years of care by my People, all occurring in my lifetime, on my watch. The Ancestors cannot be pleased. I have seen old-growth ponderosa pines, incense cedars, Douglas firs, and Santa Lucia firs disappear from whole valleys because of damaging wildfires. My grandfather and my father warned the Forest Service repeatedly that this would happen unless fire was returned to the land.

You would think that after so many firestorms raging through Big Sur in recent decades, and all the lost homes and forests, that our community would try a different approach, one that is more open to fire, working with fire not against it. But fire is still being suppressed throughout most of our region. Between the many locals that understand the importance of healthy fire but don't have the means or knowledge to put fire back on their lands, to those who hold onto the wilderness ideology that any intervention by humans is a crime against nature, who is left to take the lead?

My dad tried to take the lead, and my grandfather, but few followed. Those of us who did are carrying on the fire practices learned and refined over hundreds and even thousands of years. I've been doing it for 63 years, 64 years - nearly since birth. Our fires were never large. Sometimes they would be thirteen acres, or forty acres, or four hundred acres. Probably the biggest one my dad ever did was about a thousand acres. But we burned every year.

Then in the 1970s the authorities stopped us from burning, writing us citations. Now look where we are at. In just twenty years we have lost the majority of our big trees, and many others are dying. The big grandfather oaks are dying because of all the little oaks growing like weeds around them. Redwoods too. Fire must be returned to the land and there are people like me and other Native brothers with that knowledge who are willing and able to do it.” - Tom Little Bear Nason, Forged by Fire: The Cultural Tending of Trees and Forests in Big Sur and Beyond

You can pick up a copy of this wonderful, concise and persuasive book here: Forged by Fire: The Cultural Tending of Trees and Forests in Big Sur and Beyond.

Living in the area for awhile, you see the mismanagement of the forests by Calfire, PGE, US Forest Service. Back to the Esselenes and others for us to see the way. Thanks for the article!

LOVE THE TREES AND A REAL TREE IS MUCH MORE THAN THE WORD TREE. OH GREAT MYSTERY!!!!!